How Does The Creature Learn About The Family In Frankenstein

| Frankenstein'south monster | |

|---|---|

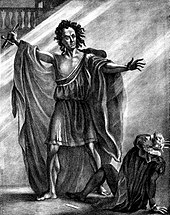

Steel engraving (993 × 78 mm), for the frontispiece of the 1831 revised edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London | |

| First advent | Frankenstein; or, The Mod Prometheus |

| Created by | Mary Shelley |

| Portrayed by | Boris Karloff Bela Lugosi Glenn Strange Christopher Lee Robert De Niro Kevin James Xavier Samuel |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | "Frankenstein", "The Monster", "The Creature", "The Wretch", "Adam Frankenstein" and others |

| Species | Simulacrum human |

| Gender | Male |

| Family unit | Victor Frankenstein (creator) Helpmate of Frankenstein (companion/predecessor; in different adaptions) |

Frankenstein'south monster or Frankenstein's creature, sometimes referred to as only "Frankenstein",[1] is an English fictional character who beginning appeared in Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Shelley'due south title thus compares the monster's creator, Victor Frankenstein, to the mythological character Prometheus, who fashioned humans out of clay and gave them fire.

In Shelley's Gothic story, Victor Frankenstein builds the creature in his laboratory through an ambiguous method based on a scientific principle he discovered. Shelley describes the monster equally 8 feet (240 cm) tall and terribly hideous, but emotional. The monster attempts to fit into human society but is shunned, which leads him to seek revenge against Frankenstein. According to the scholar Joseph Carroll, the monster occupies "a border territory between the characteristics that typically define protagonists and antagonists".[ii]

Frankenstein'due south monster became iconic in popular civilization, and has been featured in diverse forms of media, including films, television receiver series, merchandise and video games. The most popularly recognized versions are the film portrayals by Boris Karloff in the 1931 film Frankenstein, the 1935 sequel Helpmate of Frankenstein, and the 1939 sequel Son of Frankenstein.

Names [edit]

The player T. P. Cooke equally the monster in an 1823 stage product of Shelley'due south novel

Mary Shelley's original novel never gives the monster a name, although when speaking to his creator, Victor Frankenstein, the monster does say "I ought to be thy Adam" (in reference to the get-go human created in the Bible). Frankenstein refers to his creation as "fauna", "fiend", "spectre", "the dæmon", "wretch", "devil", "thing", "existence", and "ogre".[3] Frankenstein's creation referred to himself every bit a "monster" at least one time, as did the residents of a village who saw the creature towards the end of the novel.

As in Shelley's story, the fauna's namelessness became a central part of the stage adaptations in London and Paris during the decades after the novel's beginning appearance. In 1823, Shelley herself attended a performance of Richard Brinsley Peake's Presumption, the first successful stage adaptation of her novel. "The play bill amused me extremely, for in the listing of dramatis personae came _________, by Mr T. Cooke," she wrote to her friend Leigh Hunt. "This nameless style of naming the unnameable is rather good."[4]

Within a decade of publication, the name of the creator—Frankenstein—was used to refer to the creature, but it did not get firmly established until much subsequently. The story was adapted for the stage in 1927 past Peggy Webling,[v] and Webling'south Victor Frankenstein does give the animal his proper name. However, the beast has no proper noun in the Universal film series starring Boris Karloff during the 1930s, which was largely based upon Webling'southward play.[6] The 1931 Universal film treated the beast's identity in a similar mode as Shelley's novel: in the opening credits, the character is referred to merely as "The Monster" (the actor's proper name is replaced by a question marking, but Karloff is listed in the endmost credits).[7] However, in the sequel Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the frame narration by a grapheme representing Shelley'due south friend Lord Byron does refer to the monster equally Frankenstein, although this scene takes place not quite in-universe. Nevertheless, the animate being soon enough became best known in the popular imagination as "Frankenstein". This usage is sometimes considered erroneous, but some usage commentators regard the monster sense of "Frankenstein" as well-established and non an fault.[8] [9]

Modern practice varies somewhat. For instance, in Dean Koontz's Frankenstein, start published in 2004, the beast is named "Deucalion", after the grapheme from Greek mythology, who is the son of the Titan Prometheus, a reference to the original novel's title. Another case is the 2nd episode of Showtime's Penny Dreadful, which first aired in 2014; Victor Frankenstein briefly considers naming his creation "Adam", before deciding instead to let the monster "selection his own name". Thumbing through a volume of the works of William Shakespeare, the monster chooses "Proteus" from The Two Gentlemen of Verona. It is later revealed that Proteus is actually the second monster Frankenstein has created, with the first, abandoned creation having been named "Caliban", from The Storm, by the theatre player who took him in and later, after leaving the theatre, named himself after the English language poet John Clare.[10] Another example is an attempt by Randall Munroe of webcomic xkcd to make "Frankenstein" the canonical name of the monster, by publishing a short derivative version which directly states that it is.[xi] In The Strange Case of the Alchemist's Girl, the 2017 novel by Theodora Goss, the animate being is named Adam.[12]

Shelley'southward plot [edit]

Close-up of Charles Ogle equally the monster in Thomas Edison's Frankenstein (1910)

Victor Frankenstein builds the creature over a two-year flow in the attic of his boarding business firm in Ingolstadt after discovering a scientific principle which allows him to create life from non-living matter. Frankenstein is disgusted past his creation, still, and flees from information technology in horror. Frightened, and unaware of his own identity, the monster wanders through the wilderness.

He finds solace abreast a remote cottage inhabited past an older, blind man and his ii children. Eavesdropping, the brute familiarizes himself with their lives and learns to speak, whereby he becomes an eloquent, educated, and well-mannered individual. During this time, he also finds Frankenstein's periodical in the pocket of the jacket he plant in the laboratory and learns how he was created. The animal eventually introduces himself to the family's blind father, who treats him with kindness. When the residue of the family returns, however, they are frightened of him and drive him away. Enraged, the brute feels that humankind is his enemy and begins to hate his creator for abandoning him. Yet, although he despises Frankenstein, he sets out to find him, believing that he is the but person who will help him. On his journey, the animal rescues a young girl from a river but is shot in the shoulder by the child's father, believing the brute intended to harm his kid. Enraged past this final act of cruelty, the creature swears revenge on humankind for the suffering they have caused him. He seeks revenge against his creator in item for leaving him alone in a world where he is hated. Using the information in Frankenstein'south notes, the brute resolves to detect him.

The monster kills Victor'southward younger brother William upon learning of the boy's relation to his creator and makes information technology appear equally if Justine Moritz, a young woman who lives with the Frankensteins, is responsible. When Frankenstein retreats to the Alps, the monster approaches him at the summit, recounts his experiences, and asks his creator to build him a female mate. He promises, in return, to disappear with his mate and never problem humankind again, but threatens to destroy everything Frankenstein holds beloved should he neglect or refuse. Frankenstein agrees, and eventually constructs a female creature on a remote isle in Orkney, but aghast at the possibility of creating a race of monsters, destroys the female fauna before it is consummate. Horrified and enraged, the animate being immediately appears, and gives Frankenstein a final threat: "I volition exist with y'all on your wedding ceremony night."

Afterwards leaving his creator, the creature goes on to impale Victor's best friend, Henry Clerval, and later kills Frankenstein's bride, Elizabeth Lavenza, on their wedding dark, whereupon Frankenstein's father dies of grief. With nothing left to live for only revenge, Frankenstein dedicates himself to destroying his creation, and the creature goads him into pursuing him north, through Scandinavia and into Russia, staying ahead of him the unabridged way.

As they reach the Arctic Circle and travel over the pack ice of the Arctic Ocean, Frankenstein, suffering from severe exhaustion and hypothermia, comes within a mile of the creature, but is separated from him when the ice he is traveling over splits. A ship exploring the region encounters the dying Frankenstein, who relates his story to the ship'due south captain, Robert Walton. Later, the monster boards the ship, but upon finding Frankenstein dead, is overcome by grief and pledges to incinerate himself at "the Northernmost extremity of the globe". He then departs, never to exist seen again.

Advent [edit]

Frankenstein'due south monster in an editorial drawing, 1896, an allegory on the Silverite motility displacing other progressive factions in late 19th century U.S.

Shelley described Frankenstein'south monster as an 8-foot-tall (ii.4 m) fauna of hideous contrasts:

His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as cute. Beautiful! Neat God! His yellow pare scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.

A picture of the creature appeared in the 1831 edition. Early on stage portrayals dressed him in a toga, shaded, along with the monster'southward skin, a pale blue. Throughout the 19th century, the monster'southward image remained variable according to the artist.

Portrayals in motion-picture show [edit]

The all-time-known paradigm of Frankenstein's monster in pop culture derives from Boris Karloff's portrayal in the 1931 movie Frankenstein, in which he wore makeup applied and designed by Jack P. Pierce.[thirteen] Universal Studios, which released the film, was quick to secure ownership of the copyright for the makeup format. Karloff played the monster in two more Universal films, Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein; Lon Chaney Jr. took over the function from Karloff in The Ghost of Frankenstein; Bela Lugosi portrayed the role in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Human being; and Glenn Strange played the monster in the last three Universal Studios films to feature the character – House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula, and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Nonetheless, the makeup worn by subsequent actors replicated the iconic look kickoff worn past Karloff. The image of Karloff's face is currently owned past his girl's company, Karloff Enterprises, secured for her in a lawsuit for which she was represented by chaser Bela G. Lugosi (Bela Lugosi'southward son), after which Universal replaced Karloff's features with those of Glenn Strange in virtually of their marketing. In 1969, the New York Times mistakenly ran a photo of Strange for Karloff'due south obituary.

Since Karloff's portrayal, the creature about always appears every bit a towering, undead-like figure, often with a flat-topped angular head and bolts on his neck to serve as electrical connectors or grotesque electrodes. He wears a dark, unremarkably tattered, accommodate having shortened coat sleeves and thick, heavy boots, causing him to walk with an awkward, stiff-legged gait (as opposed to the novel, in which he is described every bit much more flexible than a human). The tone of his skin varies (although shades of dark-green or grey are common), and his trunk appears stitched together at sure parts (such as around the neck and joints). This image has influenced the creation of other fictional characters, such every bit the Hulk.[14]

Boris Karloff in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) in a variation of the archetype 1931 motion picture version with an help from make-up creative person Jack Pierce. Karloff had gained weight since the original iteration and much of the monster's pilus has been burned off to indicate having been defenseless in a fire. The hair was gradually replaced during the course of the film to simulate information technology beginning to abound dorsum.

In the 1957 film The Curse of Frankenstein, Christopher Lee was cast as the creature. The producers Hammer Moving-picture show Productions refrained from duplicating aspects of Universal'due south 1931 film, and and so Phil Leakey designed a new look for the animate being begetting no resemblance to the Boris Karloff design created by Jack Pierce.[xv] For his performance equally the brute Lee played him as a loose-limbed and childlike, fearful and lonely, with a suggestion of beingness in pain. Author Paul Leggett describes the animal as being similar an abused child; afraid but besides violently aroused.[sixteen] Christopher Lee, was annoyed on getting the script and discovering that the monster had no dialogue, for this animate being was totally mute.[17] According to Marcus K. Harmes in contrasting Lee's animate being with the i played by Karloff, "Lee's deportment every bit the monster seem more than directly evil, to judge from the expression on his face when he bears downward on the helpless sometime bullheaded man just these are explained in the film equally psychopathic impulses caused by brain harm, not the cunning of the literary monster. Lee also evokes considerable pathos in his performance." [17] In this film the aggressive and kittenish demeanour of the monster are in contrast with that of the murdered Professor Bernstein, once the "finest brain in Europe", from whom the creature's now damaged encephalon was taken.[17] The sequels to The Expletive of Frankenstein would feature the Baron creating various dissimilar creatures, none of which would be played by Christopher Lee.

In the 1965 Toho film Frankenstein Conquers the Globe, the heart of Frankenstein'due south monster was transported from Germany to Hiroshima equally World War Two neared its end, only to be irradiated during the atomic bombing of the city, granting it miraculous regenerative capabilities. Over the ensuing xx years, information technology grows into a complete human child, who then apace matures into a giant, 20-metre-tall man. Afterwards escaping a laboratory in the urban center, he is blamed for the crimes of the burrowing kaiju Baragon, and the two monsters face off in a showdown that ends with Frankenstein's monster victorious, though he falls into the depths of the Globe after the ground collapses below his feet.

In the 1973 TV miniseries Frankenstein: The True Story, in which the creature is played by Michael Sarrazin, he appears as a strikingly handsome man who later degenerates into a grotesque monster due to a flaw in the cosmos process.

In the 1994 film Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the creature is played by Robert De Niro and has an appearance closer to that described in the original novel, though this version of the creature possesses balding gray hair and a body covered in bloody stitches. He is, equally in the novel, motivated by pain and loneliness. In this version, Frankenstein gives the monster the brain of his mentor, Doctor Waldman, while his torso is fabricated from a human who killed Waldman while resisting a vaccination. The monster retains Waldman's "trace memories" that obviously help him chop-chop larn to speak and read.

In the 2004 picture Van Helsing, the monster is shown in a modernized version of the Karloff pattern. He is 8 to 9 feet (240–270 cm) alpine, has a foursquare bald head, gruesome scars, and stake green skin. The electric origin of the creature is emphasized with one electrified dome in the dorsum of his head and another over his heart, and he also has hydraulic pistons in his legs, with the design beingness like to that of a steam-punk cyborg. Although not as eloquent equally in the novel, this version of the creature is intelligent and relatively irenic.

In 2004, a TV miniseries adaptation of Frankenstein was made by Hallmark. Luke Goss plays the creature. This accommodation more closely resembles the monster as described in the novel: intelligent and clear, with flowing, dark hair and watery eyes.

The 2005 movie Frankenstein Reborn portrays the creature as a paraplegic man who tries to regain the power to walk by having a computer scrap implanted. Instead, the surgeon kills him and resurrects his corpse equally a reanimated zombie-like creature. This version of the creature has stitches on his face where he was shot, strains of brown pilus, blackness pants, a nighttime hoodie, and a black jacket with a brown fur collar.

The 2014 Tv series Penny Dreadful besides rejects the Karloff blueprint in favour of Shelley'southward description. This version of the creature has the flowing dark hair described by Shelley, although he departs from her clarification by having pale grey pare and obvious scars along the right side of his confront. Additionally, he is of average height, beingness fifty-fifty shorter than other characters in the serial. In this serial, the monster names himself "Caliban", after the character in William Shakespeare's The Storm. In the serial, Victor Frankenstein makes a 2nd and third brute, each more duplicate from normal human beings.

Personality [edit]

Every bit depicted by Shelley, the monster is a sensitive, emotional brute whose just aim is to share his life with another sentient existence like himself. The novel portrayed him equally versed in Paradise Lost, Plutarch's Lives, and The Sorrows of Young Werther, books he finds later on having learnt language.

From the beginning, the monster is rejected by everyone he meets. He realizes from the moment of his "nativity" that even his own creator cannot stand up the sight of him; this is obvious when Frankenstein says "…one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped…".[18] : Ch.5 Upon seeing his own reflection, he realizes that he besides is repulsed by his appearance. His greatest desire is to find love and credence; but when that want is denied, he swears revenge on his creator.

The monster is a vegetarian. While speaking to Frankenstein, he tells him, "My food is not that of man; I practice not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment...The picture I nowadays to you lot is peaceful and human."[19] At the time the novel was written, many writers, including Percy Shelley in A Vindication of Natural Diet,[20] argued that practicing vegetarianism was the morally right thing to practise.[21]

Contrary to many film versions, the creature in the novel is very articulate and eloquent in his speech. Virtually immediately later his creation, he dresses himself; and inside 11 months, he can speak and read German and French. Past the stop of the novel, the brute is able to speak English fluently besides. The Van Helsing and Penny Dreadful interpretations of the character have similar personalities to the literary original, although the latter version is the only one to retain the character'south fierce reactions to rejection. In the 1931 film adaptation, the monster is depicted as mute and bestial; it is unsaid that this is considering he is accidentally implanted with a criminal's "abnormal" brain. In the subsequent sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, the monster learns to speak, albeit in brusk, stunted sentences. However, his intelligence is implied to exist adequately adult, since what little dialogue he speaks suggests he has a world-weary attitude to life, and a deep understanding of his unnatural state. When rejected past his bride, he briefly goes through a suicidal state and attempts suicide, blowing up the laboratory he is in. In the second sequel, Son of Frankenstein, the creature is once again rendered inarticulate. Following a brain transplant in the third sequel, The Ghost of Frankenstein, the monster speaks with the voice and personality of the brain donor. This was continued subsequently a fashion in the scripting for the quaternary sequel, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, only the dialogue was excised before release. The monster was finer mute in later sequels, although he refers to Count Dracula every bit his "master" in Abbott and Costello Run into Frankenstein. The monster is oft portrayed as being afraid of fire, although he is not afraid of it in the novel, fifty-fifty using burn down to destroy himself.

The monster as a metaphor [edit]

Scholars sometimes wait for deeper meaning in Shelley's story, and accept drawn an illustration between the monster and a motherless child; Shelley'due south own female parent died while giving birth to her.[22] The monster has also been analogized to an oppressed class; Shelley wrote that the monster recognized "the segmentation of property, of immense wealth and squalid poverty".[22] Others run into in the monster the dangers of uncontrolled scientific progress,[23] especially as at the fourth dimension of publishing; Galvanism had convinced many scientists that raising the expressionless through use of electrical currents was a scientific possibility.

Another proposal is that Victor Frankenstein was based on a real scientist who had a like name, and who had been called a modern Prometheus – Benjamin Franklin. Accordingly, the monster would represent the new nation that Franklin helped to create out of remnants left by England.[24] Victor Frankenstein's father "made also a kite, with a wire and string, which drew downwardly that fluid from the clouds," wrote Shelley, similar to Franklin's famous kite experiment.[24]

Racial interpretations [edit]

In discussing the physical description of the monster, in that location has been some speculation about the potential his design is rooted in common perceptions of race during the 18th century. Iii scholars have noted that Shelley'due south description of the monster seems to be racially coded; one argues that, "Shelley's portrayal of her monster drew upon contemporary attitudes towards not-whites, in particular on fears and hopes of the abolitionism of slavery in the West Indies."[25] Of form, at that place is no evidence to suggest that the monster's depiction is meant to mimic whatever race, and such interpretations are based in personal conjectural interpretations of Shelley'south text rather than remarks from herself or any known intentions of the author.

Karloff in 1935 teaser ad

In her article "Frankenstein, Racial Science, and the Yellow Peril,"[26] Anne Mellor claims that the monster's features share a lot in common with the Mongoloid race. This term, now out of fashion and carrying some negative connotations, is used to describe the "yellow" races of Asia as distinct from the Caucasian or white races. To support her claim, Mellor points out that both Mary and Percy Shelley were friends with William Lawrence, an early on proponent of racial science and someone who Mary "continued to consult on medical matters and [met with] socially until his death in 1830."[26] While Mellor points out to allusions to Orientalism and the Yellow Peril, John Malchow in his article "Frankenstein'south Monster and Images of Race in Nineteenth-Century Britain"[25] explores the possibility of the monster either beingness intentionally or unintentionally coded as black. Malchow argues that the monster's depiction is based in an 18th-century agreement of "popular racial discourse [which] managed to conflate such descriptions of detail ethnic characteristics into a full general image of the "Negro" body in which repulsive features, beast-similar strength and size of limbs featured prominently."[25] Malchow makes information technology clear that it is hard to tell if this declared racial allegory was intentional on Shelley'south function or if information technology was inspired past the society she lived in (or if it exists in the text at all outside of his interpretation), and he states that "There is no clear proof that Mary Shelley consciously set out to create a monster which suggested, explicitly, the Jamaican escaped slave or maroon, or that she drew directly from whatsoever person cognition of either planter or abolitionist propaganda."[25] In addition to the previous interpretations, Karen Lynnea Piper argues in her article, "Inuit Diasporas: Frankenstein and the Inuit in England" that the symbolism surrounding Frankenstein's monster could stem from the Inuit people of the arctic. Piper argues that the monster accounts for the "missing presence" of any indigenous people during Waldon's trek, and that he represents the fear of the savage, lurking on the outskirts of civilization.[27]

Portrayals [edit]

| Actor | Year | Production |

|---|---|---|

| Thomas Cooke | 1823 | Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein (stage play) |

| Charles Stanton Ogle | 1910 | Frankenstein |

| Percy Standing | 1915 | Life Without Soul |

| Umberto Guarracino | 1920 | The Monster of Frankenstein |

| Boris Karloff | 1931 | Frankenstein |

| 1935 | Helpmate of Frankenstein | |

| 1939 | Son of Frankenstein | |

| 1962 | Route 66': "Cadger's Leg and Owlet'south Wing" (Television receiver serial episode) | |

| Dale Van Sickel | 1941 | Hellzapoppin |

| Lon Chaney Jr. | 1942 | The Ghost of Frankenstein [28] |

| 1952 | Tales of Tomorrow: "Frankenstein" (TV series episode) | |

| Bela Lugosi | 1943 | Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man |

| Glenn Foreign | 1944 | The House of Frankenstein |

| 1945 | House of Dracula | |

| 1948 | Abbott and Costello Run across Frankenstein | |

| Gary Conway | 1957 | I Was a Teenage Frankenstein |

| Christopher Lee | The Curse of Frankenstein | |

| Gary Conway | 1958 | How to Make a Monster |

| Michael Gwynn | The Revenge of Frankenstein | |

| Mike Lane | Frankenstein 1970 | |

| Harry Wilson | Frankenstein's Daughter | |

| Don Megowan | Tales of Frankenstein (TV pilot) | |

| Danny Dayton | 1963 | Mack and Myer for Rent: "Monstrous Merriment" (TV serial episode) |

| Kiwi Kingston | 1964 | The Evil of Frankenstein |

| Fred Gwynne | The Munsters (as "Herman Munster") | |

| Koji Furuhata | 1965 | Frankenstein Conquers the Earth |

| John Maxim | Doctor Who: "The Hunt" (TV series episode) | |

| Robert Reilly | Frankenstein Meets the Infinite Monster | |

| Yû Sekida and Haruo Nakajima | 1966 | The War of the Gargantuas |

| Allen Swift | 1967 | Mad Monster Party? |

| 1972 | Mad Mad Mad Monsters | |

| Susan Denberg | 1967 | Frankenstein Created Woman |

| Robert Rodan | Dark Shadows | |

| David Prowse | 1967 | Casino Royale |

| 1970 | The Horror of Frankenstein | |

| 1974 | Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell | |

| Freddie Jones | 1969 | Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed |

| Manuel Leal | Santo y Blueish Demon contra los monstruos (as "Franquestain") | |

| Howard Morris | 1970 | Groovie Goolies (as "Frankie") |

| John Bloom and Shelley Weiss | 1971 | Dracula vs. Frankenstein |

| Xiro Papas | 1972 | Frankenstein 80 |

| Bo Svenson | 1973 | The Broad World of Mystery "Frankenstein" (TV serial episode) |

| José Villasante | The Spirit of the Beehive | |

| Michael Sarrazin | Frankenstein: The True Story | |

| Srdjan Zelenovic | 1974 | Flesh for Frankenstein |

| Peter Boyle | Young Frankenstein | |

| Per Oscarsson | 1976 | Terror of Frankenstein |

| Mike Lane | Monster Squad | |

| Jack Elam | 1979 | Struck by Lightning |

| John Schuck | The Halloween That Most Wasn't | |

| Peter Cullen | 1984 | The Transformers |

| David Warner | Frankenstein (Goggle box pic) | |

| Clancy Brown | 1985 | The Bride |

| 2020 | DuckTales | |

| Tom Noonan | 1987 | The Monster Squad |

| Paul Naschy | El Aullido del Diablo | |

| Chris Sarandon | Frankenstein (TV flick) | |

| Phil Hartman | 1987–1996 | Sat Night Live [29] [30] |

| Zale Kessler | 1988 | Scooby-Doo and the Ghoul Schoolhouse |

| Jim Cummings | Scooby-Doo! and the Reluctant Werewolf | |

| Craig Armstrong | 1989 | The Super Mario Bros. Super Testify! |

| Nick Brimble | 1990 | Frankenstein Unbound |

| Randy Quaid | 1992 | Frankenstein |

| Robert De Niro | 1994 | Mary Shelley's Frankenstein |

| Deron McBee | 1995 | Monster Mash: The Movie |

| Peter Crombie | 1997 | House of Frankenstein |

| Thomas Wellington | The Creeps | |

| Frank Welker | 1999 | Alvin and the Chipmunks Come across Frankenstein |

| Shuler Hensley | 2004 | Van Helsing |

| Luke Goss | Frankenstein | |

| Vincent Perez | Frankenstein | |

| Joel Hebner | 2005 | Frankenstein Reborn |

| Julian Bleach | 2007 | Frankenstein |

| Shuler Hensley | Young Frankenstein | |

| Scott Adsit | 2010 | Mary Shelley's Frankenhole |

| Benedict Cumberbatch | 2011 | Frankenstein |

| Jonny Lee Miller | ||

| Tim Krueger | Frankenstein: Day of the Animal | |

| David Harewood | Frankenstein'south Wedding | |

| Kevin James | 2012 | Hotel Transylvania |

| 2015 | Hotel Transylvania ii | |

| 2018 | Hotel Transylvania 3: Summer Vacation | |

| David Gest | 2012 | A Nightmare on Lime Street [31] |

| Marker Hamill | Uncle Grandpa | |

| Roger Morrissey | 2013 | The Frankenstein Theory |

| Chad Michael Collins | One time Upon a Time | |

| Aaron Eckhart | 2014 | I, Frankenstein |

| Rory Kinnear | Penny Dreadful | |

| Dee Bradley Baker | Winx Lodge (in "A Monstrous Crush") | |

| Michael Gladis | 2015 | The Librarians (in "And the Cleaved Staff") |

| Spencer Wilding | Victor Frankenstein | |

| Xavier Samuel | Frankenstein | |

| Kevin Michael Richardson | Rick and Morty | |

| Brad Garrett | 2016 | Apple holiday commercial |

| John DeSantis | 2017 | Escape from Mr. Lemoncello's Library |

| Ai Nonaka | Fate/Apocrypha | |

| Grant Moninger | Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles | |

| Skylar Astin | 2019 | Vampirina |

| Will Ferrell | Drunk History | |

| Brad Abrell[32] | 2022 | Hotel Transylvania: Transformania |

Encounter too [edit]

- Frankenstein in popular culture

- List of films featuring Frankenstein'due south monster

- Allotransplantation, the transplantation of trunk parts from one person to another

- Xenotransplantation – Transplantation of cells or tissue across species

References [edit]

- ^ For case, in Peggy Webling's 1927 stage play, and the 2004 film, Van Helsing.

- ^ Carroll, Joseph; Gottschall, Jonathan; Johnson, John A.; Kruger, Daniel J. (2012). Graphing Jane Austen: The Evolutionary Footing of Literary Meaning. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN978-1137002402.

- ^ Baldick, Chris (1987). In Frankenstein's shadow: myth, monstrosity, and nineteenth-century writing. Oxford: Clarendon Printing. ISBN9780198117261.

- ^ Haggerty, George E. (1989). Gothic Fiction/Gothic Form. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 37. ISBN978-0271006451.

- ^ Hitchcock, Susan Tyler (2007). Frankenstein: a cultural history. New York City: W. West. Norton. ISBN9780393061444.

- ^ Young, William; Young, Nancy; Butt, John J. (2002). The 1930s . Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 199. ISBN978-0313316029.

- ^ Schor, Esther (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Printing. p. 82. ISBN978-0521007702.

- ^ Evans, Bergen (1962). Comfortable Words . New York Metropolis: Random House.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (1998). A dictionary of modern American usage. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN9780195078534.

- ^ Crow, Dennis (19 October 2016). "Penny Dreadful: The Most Faithful Version of the Frankenstein Fable". Den of Geek. London, England: Dennis Publishing. Retrieved thirteen July 2017.

- ^ "Frankenstein". xkcd . Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Teitelbaum, Ilana (13 Oct 2018). "Tales of Monstrous Women: "The Strange Case of the Alchemist's Daughter" and "European Travel for the Monstrous Gentlewoman" by Theodora Goss". Los Angeles Review of Books . Retrieved 25 Nov 2020.

- ^ Mank, Gregory William (eight March 2010). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration, with a Complete Filmography of Their Films Together. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-5472-3.

- ^ Weinstein, Simcha (2006). Upward, Up, and Oy Vey!: how Jewish history, civilization, and values shaped the comic book superhero. Baltimore, Maryland: Leviathan Press. pp. 82–97. ISBN978-1-881927-32-7.

- ^ Rigby, Jonathan (2000). English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. ISBNi-903111-01-3.

- ^ Legget, Paul (2018). Adept Versus Evil in the Films of Christopher Lee. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers Ltd. pp. 09–12. ISBN978-1-476669-63-two.

- ^ a b c Harmes, Marcus One thousand (2015). The Expletive of Frankenstein. Columbia University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN9780993071706.

- ^ Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft (1818). "Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus". Retrieved three November 2012 – via Gutenberg Projection.

- ^ Irvine, Ian. "From Frankenstein's monster to Franz Kafka: vegetarians through history". Retrieved 5 Oct 2020.

- ^ Shelley, Percy. A Vindication of Natural Nutrition. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Morton, Timothy (21 September 2006). The Cambridge Companion to Shelley. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN9781139827072.

- ^ a b Milner, Andrew (2005). Literature, Culture and Lodge. New York Metropolis: NYU Press. pp. 227, 230. ISBN978-0814755648.

- ^ Coghill, Jeff (2000). CliffsNotes on Shelley's Frankenstein. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 30. ISBN978-0764585937.

- ^ a b Young, Elizabeth (2008). Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor. New York City: NYU Press. p. 34. ISBN978-0814797150.

- ^ a b c d Malchow, H Fifty. "Frankenstein's Monster and Images of Race in Nineteenth-Century Britain." Past & Nowadays, No. 139, May 1993, pp. 90–130.

- ^ a b Mellor, Anne K. "Frankenstein, Racial Scientific discipline, and the Yellowish Peril" Frankenstein: Second Edition, 2012, pp. 481

- ^ Piper, Karen Lynnea. "Inuit Diasporas: Frankenstein and the Inuit in England." Romanticism, vol. 13 no. ane, 2007, p. 63-75. Projection MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/214804.

- ^ Chaney also reprised the part, uncredited, for a sequence in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein due to the character's assigned histrion, Glenn Foreign, being injured.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Paul Simon: 12/xix/87: Succinctly Speaking".

- ^ "Watch Weekend Update: Frankenstein on Congressional Budget Cuts from Saturday Night Live on NBC.com".

- ^ "A Nightmare On Lime Street – Royal Court Theatre Liverpool". Royal Court Liverpool.

- ^ Verboven, Jos (17 May 2021). "Trailer Park: 'Hotel Transylvania: Transformania'". Scifi.radio. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

External links [edit]

- Literary give-and-take of the argument of Frankenstein

- 2014 Irish Examiner commodity

How Does The Creature Learn About The Family In Frankenstein,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein%27s_monster

Posted by: brousseauvedge1990.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Does The Creature Learn About The Family In Frankenstein"

Post a Comment